What Is Close to the Czech Heart

We probably won’t strike you as the most emotional or patriotic of nations, yet there are some things we ARE very fond of and emotional about. Only we don’t express it very easily. And we only realize it ourselves when someone says something negative about them, and we find ourselves defending them fiercely!

Here goes:

- Beer (and wine, and Kofola)

- Film fairy-tales

- Chateaus, castles and other places of interest

- Charity

- Saturnin

- Some 1930’s personalities

- Czech comedy films

- History: Middle Ages

- Hiking & canoeing (& swimming & skiing), mountains & forests

- Jára Cimrman and humour

-

Beer (and wine, and Kofola). This is the stereotypical one that’s actually true. We love our beer. It’s cheap and good and there are hundreds of breweries here. We can sit in a pub for hours and chat with friends without getting drunk because Czech beer has low levels of alcohol. It’s the default drink, the universal drink – as witnessed by the fact that the Czech name for it, “pivo”, simply means “something to drink”.

120 years ago, my town had 7,000 inhabitants and 80 inns and all of them had their own breweries. 80 breweries in one small town. Imagine?

By the way, did you know that the word “Budweiser” is Czech? Well, German, really… It’s the German name for the town of České Budějovice. And České Budějovice means “the Bohemian town that belongs to Budivoj”. And Budivoj is an old Czech name that means “the one who awakens the army”. So the American beer called Bud actually means “waking up” 😊

There’s a brewery in České Budějovice that’s been making Budweiser beer since 1895.

http://www.budejovickybudvar.cz/en/o-spolecnosti/budejovicky-budvar.html#znamkopravni-spory

But few non-Czechs know that it’s not just beer with us. We have several wine-making regions, too—mostly located in the South-Eastern part of the country There, you can insult beer till your throat gets sore and nobody will mind, but say one word against their wine and you’ll get punched in the face. Or—to follow the stereotype that Czech wine makers are friendly—you will be sent to a wine cellar and proven wrong 😊

We don’t make enough wine to export, but still are proud of it. It wins international competitions so it can’t be bad 😊 If you like heavy, rich, sweet wines, don’t drink it, though. As it is grown in a relatively cold climate, it’s light and not very sweet.

Traditional wine cellars in Plže, situated in the Czech region of Moravia. Picture by Wikimedia Commons user Mercy.

And even fewer non-Czechs know that we have our own version of Coca Cola, called Kofola, that contains liquorice and its taste is more bitter than Coke’s. It isn’t strictly considered a traditional Czech drink, as it’s too similar to Coca-Cola, but most Czechs drink it and love it.

Kofola bottle and glass. Picture by Wikimedia Commons user Themightyquill.

“Slivovica”, plum brandy, is a matter of the heart in the Eastern part of the CzR.

The country is basically divided into three regions: the Beer Region, the Wine Region and the Slivovica Region 😊

-

Film fairy-tales. Have you watched Three Hazelnuts for Cinderella (Tři oříšky pro Popelku, 1973)? If not, I recommend you do. It’s one of the rare cases where Czechs were able to communicate to the world what they feel strongly about.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tři_oříšky_pro_Popelku

Together with this, there goes a certain fondness for the leading actress, Libuše Šafránková. She’s in her 60’s now but still kind, beautiful, playful and graceful. And a decent person. Some people say they like her sister, Miroslava Šafránková, more she’s kind, beautiful, graceful and decent, too :-) Watching film fairy-tales and liking the Šafránková sisters is very much a Czech thing.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libuše_Šafránková

But there are heaps and heaps of other film fairy-tales to choose from. I’m not sure about the numbers but I’d hazard a guess that there’ve been at least 5 film fairy-tales made every year since 1968. And almost everyone watches them at Christmas.

The plots are very specific—in fact, a Czech film fairy-tale is a specific genre. They don’t have many supernatural elements, they’re more like romantic-poetic-adventurous comedies. Unlike Disney fairy-tales, they’re not as focused on physical action, fighting or personal stories of the heroes.

Their main focus is justice, love, humour, beauty and hope. Often also friendship or love for nature / animals.

If you understand some Czech or have someone to translate for you, here are the most famous ones:

Pyšná princezna (a beautiful romantic film, which holds the record of being the film that the biggest number of Czechs saw in cinemas)

Byl jednou jeden král (sort of a serious, deep comedy)

Princezna se zlatou hvězdou (romantic, comedy)

Šíleně smutná princezna (romantic, comedy)

Princ Bajaja (romantic and adventurous - by the same author as Three Hazelnuts for Cinderella)

Zlatovláska (romantic and adventurous)

Jak se budí princezny (romantic and adventurous)

Princ a večernice (romantic and adventurous)

Třetí princ (adventurous, dark)

S čerty nejsou žerty (adventurous, comedy)

Lotrando a Zubejda (comedy, with a creative, funny, rich vocabulary)

-

Chateaus, castles and other places of interest—regional tourism, in short. Have you noticed that a lot of the fairy-tales I’ve listed contain the words “princezna” (princess), “princ” (prince) and “král” (king)?

If you’ve ever seen our castles and chateaus, you understand why. They’re simply so fairy-tale-like that it would be a shame not to use them in films about royalty. See for yourselves 😊

The country has been densely inhabited for centuries, so there is much to see here. Churches, mediaeval underground labyrinths, museums, Jewish cemeteries, spectacular rock formations, observation towers, zoos, WW2 bunkers… We’ve received so much money from the EU to restore the places of interest that regional tourism has become immensely popular. You can literally just point at a random spot in the map, go there and find a place of interest. We have several excellent regional tourism websites like www.hrady.cz or www.itras.cz. As you don’t need much money to travel to places of interest, almost everybody does that on weekends.

This is new for us. But it builds on the tradition of regional patriotism that’s been around for centuries. And our care for… houses, gardens… places. When we were celebrating the 100th independence anniversary in 2018, it became clear that regional places of interest are a source of huge pride for us.

-

Charity. I’ve read somewhere that Czechs give more money to charity organizations every year than Poles, and I mean more not just in relation to the number of inhabitants. When you realize that there are 10.5 millions of Czechs and 38.5 millions of Poles, this is actually quite impressive.

Our version of Dancing with the Stars includes a charity evening when the celebrities dance with people on wheelchairs. In the 2018 season charity episode, we collected 15.1 million CZK during a two-hour evening.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6vczv8mt6Us&t=1s

My personal theory is that fairy-tales and charity donations are what makes up for the lack of religion in the CzR. Poles are Catholic, so they don’t need any fairy-tales or charity donations to fulfil their need of justice and hope.

-

Saturnin. There was a popular poll “Book of my Heart” a couple of years ago. And this book won. It’s a humourous novel, written during WWII by Zdeněk Jirotka, who isn’t very well-known as a writer but will live forever in this brilliant book. It’s been translated to English but unfortunately, most of its charm is in the Czech language.

But I think you could very well enjoy the miniseries that was made in 1994 and is pretty close to the book. It was also shortened to a film, but when you don’t know the book, the film is hard to understand because there are some things left out. So I recommend the mini-series.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saturnin_(novel)

What is the book about?

A 30-year-old guy in the 1930’s who works in an office and isn’t exactly what you’d call imaginative or adventurous. But one day, on a whim, he hires a servant who is the exact opposite of him. This servant’s name is Saturnin and his hobby is telling everyone that his employer is a lion- and crocodile-hunter who lives in a houseboat. Then he actually makes him move to a houseboat.

Most of the book takes place during a summer holiday where the young guy, his servant Saturnin, his grandfather, his extremely annoying aunt who only speaks in proverbs, her son and a beautiful girl get stuck in a house in mountains that’s been cut off from the rest of the world by a flood. But rest assured that Saturnin will make sure nobody is bored…

I’m not allowed to share any pictures from the mini-series but you can view them here:

-

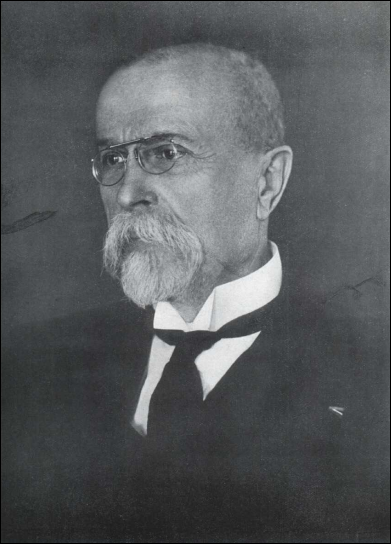

Some 1930’s personalities. Our first President T.G. Masaryk and writer Karel Čapek—not everyone likes them, but most Czechs admit they were brilliant.

Whatever famous Czech you may have heard about abroad—Franz Kafka, Václav Havel, Milan Kundera, Jaroslav Hašek and his Švejk—please realize that those are perceived as famous Czechs by non-Czechs. They have a huge place in our history, but Masaryk and Čapek (whose brother created the word “robot”, by the way)—these are the ones at the core of Czech identity itself.

If I was to sum up their heritage in two sentences, it would be “no life is unimportant” and “it is a grand thing to be human”.

Writer Karel Čapek (1890-1938). Picture by Wikimedia Commons user GoogleMe.

And it’s not just T.G. Masaryk and Karel Čapek. In the 1930’s, Czechoslovakia was overflowing with excellent actors, writers, journalists… The 1930’s are perceived as a sort of a Golden Age of Czechs and Slovaks.

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, the first president after Czechoslovakia became a country independent of Austria-Hungary in 1918. Picture by Wikimedia Commons user Realismadder.

-

Czech(oslovak) comedy films. The 1930’s, together with 1960’s and 1970’s, were the Golden Ages of Czechoslovak Cinema, too. And out of the hundreds of films that were made in those times, it’s comedies that gained popularity.

Virtually all Czechs are able to quote tens and tens of funny lines from those films and are so passionate about them that if someone claimed not to like these films, they would probably exclaim: “This isn’t possible, you can’t have been born in Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic. Were you perhaps born on Mars?”

Luckily, these comedies are so diverse that everyone can find their favourite one.

Absurd, parodic and mildly sarcastic humour is typical for these films, sometimes classy, sometimes vulgar. They’re similar to some Russian comedies, but they don’t have that much of the crazy element; we don’t like extremes; it’s not “anything can happen”, the plots have clearer lines. They’re often about the lives of “common people” with some uncommon elements.

This is the part of Czech heart that’s most difficult to explain. It’s mostly the absurdity of the films that we like; the seemingly everyday and yet unexpected, the connecting of things that are not usually connected.

I’ll limit myself to listing some of the most popular and most quoted comedies. If you study Czech, I recommend watching them—they are the ultimate graduation in the Czech way of thinking 😊

Kristián (1939)

Cesta do hlubin študákovy duše (1939)

U pokladny stál… (1939)

Černý Petr (1963)

Limonádový Joe aneb Koňská opera (1964)

Na samotě u lesa (1976)

Marečku, podejte mi pero (1976)

Postřižiny (1980)

S tebou mě baví svět (1982)

Slunce, seno, jahody (1983)

Vesničko má středisková (1985)

Obecná škola (1991)

Dědictví aneb Kurvahošigutntág (1992)

Kolja (1996)

Pelíšky (1999)

-

History: Middle Ages. Most Czechs have a weird love-hate relationship with history. They’re convinced that learning about it is boring, and yet are willing to listen to 80-minute guided tours of castles and chateaus. And when a foreigner visits their town, they suddenly turn into experts on its history. I’m not exactly a historian, and still know that the town I grew up in was given official town status in 1134.

Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that 860–1620 were the years of our glory—we had Reformation before Martin Luther, we were the first country in the world to have a Protestant king, the Bible was translated to Czech before it was to English, Prague was the capital of the Holy Roman Empire for some time, Charles University (1348) was the first university east of Germany to be founded, etc. etc.

Now, after 350 years of having other countries telling us what to do, this is obviously something to remember. We love our battle re-enactments, “mediaeval” markets and workshops, castles, archery, fencing, historical costumes, mediaeval music–

-

Hiking & canoeing (& swimming & skiing), mountains & forests. I never understood why Czechs are one of the few overweight European nations. Because we like physical activities so much. Sports are huge here and we have quite a number of Olympic medallists, including the ice hockey team. We’re both a football and an ice hockey nation. It must be the beer and the huge helpings of flour-and-meat based meals, because there’s no other possible explanation for the nation that’s so crazy about physical activities being overweight.

At an English lesson that was to be the last one for the teacher before going back to the U.S., we asked her what she’s looking forward to seeing again. She said: diversity. People are much more similar to each other in the CzR than in the U.S., and she likes it, but she’s a bit tired of it.

“You Czechs are all white and if I ask you to go hiking with me in a forest next Saturday, you will all react in the same way.” And she was right! When she was saying “hiking with me in a forest”, I realized we ALL had exactly the SAME expression on our faces! “Yeah, OK, let’s go!” I felt like we were brainwashed!

Nobody forced us to like hiking and canoeing, but we still do. I only have a vague idea why this is so. I don’t know whether you’ve heard about the Canadian author Ernest Thompson Seton, but he was the one to influence our Boy Scout movement by his books about Canadian nature and First Nations people.

And because Boy Scouts were pretty big here in the 1930’s and even more so during the Communist era (though secretly and under different names), this was something that influenced us.

Why especially during the Communist era? Because learning how to hike in forests and generally how to survive and live in harmony with nature (how to cooperate, help others, know the names of all kinds of plants and animals, save someone from drowning etc.) was one of the few apolitical things you could do and feel free in.

Also, Czech forests are safe. There are only lynxes and wolves in two mountain ranges and they’re afraid of people. And we get the occasional bear wandering in from Slovakia. The forests are usually small—in several hours’ walk, you always reach a village. And there are no swamps in them. Hence the subconscious notion that forests are friendly.

And also, hiking in a forest is the best thing you can do for your health. Walking is the most natural movement for the human body, breathing in oxygen is good for disease prevention, and the aerosol trees produce contains anti-oxidants. And if you live in a busy city, the silence is great.

I can guarantee that if you venture a 5 km walk in a forest, you’ll feel like ten times happier and healthier the next day 😊

-

Jára Cimrman (and humour in general). Jára Cimrman won the BBC poll that took place in many EU countries: “Who was the greatest Czech / German / French / whatever?” The French voted for Napoleon, Brits for Winston Churchill, etc. etc.

We voted for the guy who advised Eiffel on the shape of his tower, discovered a Yetti in the Arctic, invented absolute rhyme, bikini, and dynamite ten minutes after Alfred Nobel, and found out you can’t create gold by making tobacco smoke react with water. And has streets named after him all over the CzR.

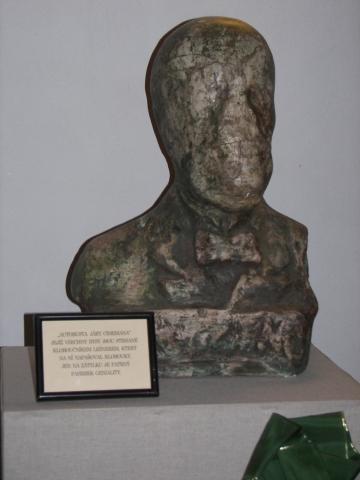

The “auto-bust” of Jára Cimrman—a statue-portrait that he made himself. Property of Žižkovské divadlo Járy Cimrmana, picture by Wikimedia Commons user Postrach (Stanislav Jelen).

But the Czech TV that organized the poll cancelled the results because guess what… Jára Cimrman never lived! BBC and the Czech TV had this weird notion that a fictitious character can’t be considered a greatest person in a nation’s history. Our response was: Who the bloody hell cares! Jára Cimrman was the greatest Czech in history, and that’s it!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jára_Cimrman

The Jára Cimrman Theatre in Prague has its English section with several British actors who are just as enthusiastic about Jára Cimrman as Czechs are. His plays have gained a slightly different flavour with the English translations but are almost as good. My favourite piece is “Hamlet without Hamlet” (a short excerpt from Cimrman’s play that he wrote for theatres with shortage of actors).

And last but not least… Czech humour. Apart from saying it’s mostly rooted in the language (we’re not great fans of Tom and Jerry type of humour)—I’m not able to describe it, come and see for yourselves 😊

It’s best illustrated by Jára Cimrman and the fact that there is the event “Total eclipse of the Sun in the Czech Republic in the year 2081” created on Facebook, and 55,000 people are planning to attend!

And those who declined the invitation are commenting “Sorry, but that’s the day the Czech astronauts are returning from Mars, I’m probably going to welcome them instead” or “Unfortunately, it’s on Sunday so I’ll be returning from my night shift”.